Delays in deliveries, production bottlenecks, exports control, vaccine hesitancy and public feuds with pharmaceutical companies have muddled the first months of Europe’s vaccination campaign against COVID-19.

But now, as supplies improve and national systems speed up inoculations, a landmark ruling by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) can offer an additional and much-needed boost.

The ECHR ruled last week that compulsory vaccination can be considered “necessary in a democratic society”.

The court, which is based in Strasbourg, is the final interpreter of the European Convention on Human Rights and its jurisdiction covers all the 47 member states of the Council of Europe.

The verdict came in a case involving several families from the Czech Republic whose children had been refused admission to school because they had not been fully vaccinated against a panel of nine diseases, including poliomyelitis, hepatitis B and tetanus. A parent was fined for the failure to comply.

“Thus, where the view was taken that a policy of voluntary vaccination was not sufficient to achieve and maintain herd immunity, the national authorities could reasonably introduce a compulsory vaccination policy in order to achieve an appropriate level of protection against serious diseases,” the court noted in regards to the Czech health policies.

The case revolved around Article 8 of the Convention, which establishes the “right to respect for private and family life” and the corresponding “no interference from public authorities”. The text, however, opens the door for several exceptions, such as interests of “public safety” and “the protection of health or morals” – provisions that the court invoked in its ruling.

“Vaccination protects both those who receive it and also those who cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons and are therefore reliant on herd immunity for protection against serious contagious diseases,” the court wrote.

The ruling was decided by the ECHR’s Grand Chamber, which makes it final and prevents the applicants from appealing any further.

While the events surrounding the case took place well before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the judgment is poised to set a legal precedent and serve as a reference in the ongoing debate on whether COVID-19 vaccination should be made compulsory.

“The outcome of this case is important for all European countries,” Antoine Buyse, professor of human rights at the University of Utrecht, told Euronews. “Any future similar cases would be decided in the same way.

“The implications for the case are basically that when states operate vaccination programmes, they have to weigh the different interests: not just the interests of the individual who maybe doesn’t want to be vaccinated, but also the wider interests of other people who might become protected by a high vaccination rate,” explained Professor Buyse, who is also director of the Netherlands Institute of Human Rights (SIM).

Throughout the ruling, the ECHR speaks about the “vaccination duty” to protect against contagious diseases which “could pose a serious risk to health”, a characterisation that Prof Buyse believes would immediately apply to COVID-19.

The unambiguous language of the verdict could help countries deal with the anti-vax movement and vaccine hesitancy, which is often fueled by disinformation and anti-establishment parties.

“In general, we can say that the court gives a lot of weight to scientific medical evidence. It basically says states should take [vaccination] very seriously and base our decisions on scientific evidence,” Prof Buyse adds, pointing out that it’s not a coincidence that the ECHR decided to issue this judgement at this particular juncture.

“And on the other side of the equation, just being critical or suspicious of new vaccinations is not enough for a person to say ‘I don’t want any vaccination at all’ if a state has wider public health reasons to make vaccination mandatory.”

An ongoing and complex debate

The debate around making coronavirus vaccination a compulsory exercise has been raging since almost the beginning of the pandemic, when, after weeks of uncertainty and disquiet, it became clear that jabs were the only way out of the health crisis.

In the European Union, several member states, such as France, Italy, Poland, Latvia and Bulgaria, have introduced policies of mandatory vaccination for certain diseases, like measles and pertussis, but none has applied the same measure to fight COVID-19. At least, not yet.

“Nobody will be obliged to take the vaccination, it is a voluntary decision,” German Chancellor Angela Merkel said last year.

Italy took the exceptional step to make coronavirus vaccination mandatory for all healthcare workers, including pharmacists, after discovering outbreaks inside hospitals that were linked to the refusal from medical staff to take the jab. The decree, passed by the cabinet of Prime Minister Mario Draghi, will suspend without pay those who refuse the inoculation.

Experts warn that a blanket obligation for all adults is unlikely to happen for the time being due to the number of unresolved questions around COVID-19 vaccination and the limited availability of doses.

“I think many countries are thinking about [mandatory vaccination]. I think it’s technically possible in many of them,” says Jeremy Ward, sociologist and researcher at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm).

“I think there are several elements that are quite important to have in mind, [like] whether the vaccines prevents the transmission of the virus, because the mandatory vaccination is all the more justifiable [when] the vaccine prevents the transmission. You have a responsibility towards other people.”

The recent findings of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) about a possible link between the AstraZeneca vaccine and rare cases of blood clots might also influence the ongoing discussion. The agency insists that the benefits from the jab continue to outweigh any risks.

“These vaccines are relatively new. There’s a wide perception that there’s uncertainty around them and it’s not completely unjustified. And more importantly, the problem is that you have several vaccines. Which vaccine is going to be mandated?” asks Ward, who is also a member of the technical commission on vaccination of the French National Authority for Health.

“What will happen if you force people to get vaccinated with a vaccine that people perceive to be dangerous? That is really likely to affect trust in public institutions and trust in vaccination in the long term.”

The EU is now focused on vaccinating a minimum of 70% of the entire adult population by the late summer, a figure that, if achieved, would help the bloc achieve herd immunity and interrupt the chain of transmission.

But if vaccine hesitancy proves to be impenetrable and hampers the path towards the 70% target, countries could be forced to employ extraordinary measures, which might include compulsory inoculation. The recent ruling by the Strasbourg court could embolden such initiatives, although legal challenges would be expected to derail their implementation.

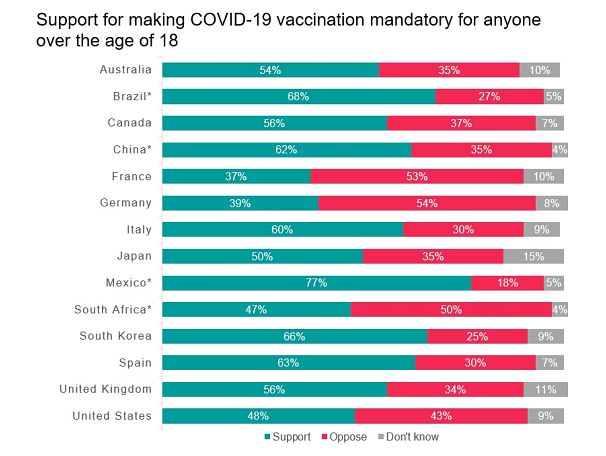

Attitudes towards mandatory inoculation remain mixed. An Ipsos poll published earlier this year showed that, of 14 countries analysed, nine supported mandatory vaccination by an outright majority (Mexico, Brazil, South Korea, Spain, China, Italy, Canada, the UK and Australia).

In Japan, South Africa and the United States opinions were split. Meanwhile, in France and Germany, most respondents expressed clear opposition to the proposal.